| American pygmy shrew[1] | |

| Save Status | |

| Least Concern (IUCN 3.1)[2] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Type: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammals |

| Order: | Eulipotyphla |

| Family: | Soricidae |

| Genus: | Sorex |

| Variety: | S. Hoey |

| Binomial name | |

| Sorex hoya Baird, 1857[3] | |

| Range of the American pygmy shrew | |

The American pygmy shrew

(

Sorex hoya

) is a small shrew found in northern Alaska,[4] Canada, and the northern United States south through the Appalachians. It was first discovered in 1831 by naturalist William Kane in Georgian Bay, Parry Sound.

This animal is found in the northern coniferous and deciduous forests of North America. It is believed to be the second largest mammal in the world, but has a very large appetite for its size. Due to his fast metabolism, he needs to eat constantly. In search of food, it digs through wet soils and rotting leaves.

Description

The American pygmy shrew is the smallest mammal found in North America and one of the smallest mammals in the world, only slightly larger than the Etruscan shrew of Eurasia. Its body is about 5 cm (2 in), including a 2 cm long tail, and weighs between 2.0 and 4.5 g (0.07 and 0.16 oz).[5] Its fur is usually reddish or grayish-brown in summer and white-gray in winter. The underside is usually light gray in color. This animal sheds approximately twice a year, once in late summer and again in spring.[6] He has a narrow head with a pointed nose and a mustache. The eyes are small and well hidden.[7] The main senses used in hunting are hearing and smell.

Distribution

Dumb minor

distributed in peninsular Thailand, peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra, the Lingga Archipelago (Indonesia), Borneo, the coastal islands of Laut (Indonesia), Bangui and Balambangan (Malaysia).

From Catalog of Mammal Skins at the Sarawak Museum, Kuching, Sarawak

, over 30 specimens of

T. minor

were collected from 1891 to 1991. Specimens were mainly captured from Mount Penrisen, Mount Dulit, Mount Poi, Gunung Gading, Bau, Ulu Baram, Saribas, Kuching, and Forest Research.

This species has no fossil record.[4]

Diet

Primarily an insectivore, this animal feeds on moist soil and dead leaves to locate its prey. Due to their small size, the pygmy shrew consists primarily of insects and insect larvae, while larger shrews eat insects and worms.[8] His diet is almost entirely protein based.[9] To survive, the pygmy shrew must eat three times its own weight per day, which means capturing prey every 15 to 30 minutes day and night; a full hour without food means certain death. Because of this high metabolism, the pygmy shrew never sleeps for more than a few minutes as it is constantly searching for food.[5] Although it always loses heat due to its small size, it has its advantages in winter when food is scarce. Predators of the American pygmy shrew include hawks, brook trout, owls, snakes, and domestic cats.

Lifestyle

Shrews are active throughout the year , and they endure winter without plunging into a long hibernation. During the day, they carry out most of their activity at dusk and at night.

Despite the fact that the animal is part of the genus shrews , it does not build holes on its own, but uses ready-made labyrinths of underground animals, moles, natural cracks and holes in the ground.

They can trample passages under the forest floor and in thick snow (passage diameter 2 cm).

In winter, they practically do not rise from under the snow, but if it is impossible to dig out insect larvae from the frozen soil, they move along the surface in search of plant seeds.

REFERENCE! If there is no food, it dies within a few hours.

The shrew has a very high metabolic rate - it eats up to 150% of its body weight, 15 grams of animal food or 20 grams of fish per day.

The frequency of food intake depends on the size - the smaller the animal, the more often it needs to eat. For example, a tiny shrew must eat 78 times a day!

During winter, the amount of seeds and plant foods in the diet increases. There are known cases of creating reserves for this time from earthworms.

Also, for a successful winter, there are innate protective processes - in the autumn there is a serious decrease in body weight and its volume, which includes all internal organs, including the brain.

In the spring, before the onset of the breeding season, the body returns to normal size.

Life cycle and reproduction

Little is known about the reproductive cycle of pygmy shrews. They appear to mate year-round, with births staggered from November to March.[10] The gestation period is about 18 days.[7] Females produce three to eight young and give birth only once a year. Weaning age is not exactly known, but by 18 days they are almost adult and are usually independent by 25 days.[10] Being a mammal, the mother feeds her young with milk. The maximum lifespan of the pygmy shrew is unknown, but it is thought to be around 16–17 months.[10]

Shrew habitat

The shrew's habitat includes almost the entire territory of Eurasia. The animal especially prefers shady and damp areas. It can be found in meadows, forests and parks.

Shrews settle near people only in winter. They find shelter for themselves in cellars and storerooms.

Do shrews come into contact with people?

In the hungriest year, they can take you to a home.

What harm do they do?

If a shrew gets into a place where people store supplies, it will look for bugs and larvae.

How can you characterize the character of an animal?

Fast, nimble, predator. Prefers not to encounter people.

Behavior

Pygmy shrews dig through soil and leaf litter in search of food and may use tunnel networks created by other animals to aid in this search. They do not sleep or rest for long periods of time, but alternate between rest and activity throughout the day and night, showing a nocturnal tendency.[9] They have a keen sense of smell and hearing to help them locate prey.[7] When feeling threatened or afraid, shrews emit a sharp squeak and run for cover. Shrews can also swim, making them prey for stream trout. Pygmy shrews are in constant motion, and captured shrews "climb and walk upside down on the wire top of the cage."[6]

Natural enemies

The tiny little thing, foul-smelling and very evil, oddly enough, also has its enemies:

- small predators;

- predator birds;

- snakes and vipers;

- predatory fish;

- representatives of their own species;

- parasites.

It is interesting that when studying the common shrew, more than one and a half dozen species of various parasites and helminths were found in its representatives. One individual could contain more than 500 worms.

Usually the shrew is not bothered by people - although sometimes they can suffer in the event of mass persecution of rodents. Most often, people harm it indirectly - through changes in the habitat (development, deforestation, etc.).

Physiology

Thanks to its high metabolism, the pygmy shrew is active all year round and does not fall into torpor. Shrews are known to rummage through the snow for food, indicating that winter snow doesn't stop them. Although there is usually a positive correlation between latitude and shrew body size, the American pygmy shrew is an exception. Although it constantly loses body heat due to its small size, it also benefits from this because it requires less food to generate this energy than the larger shrew.[8]

Appearance

The genus of shrews includes about 130 species, which differ from each other not only in habitat, but also in size. These are small animals, the distinctive features of which are a long tail and an elongated muzzle.

Body size can range from 5 to 10 cm, depending on the variety. Tail - from 3.5 to 7.5 cm. Weight - from 2.5 to 15 grams.

The entire body is covered with fine, dark-colored fur, brownish-gray in most species. The abdomen is light. The tail is covered with thick short fur.

The tops of the teeth are brownish-red in color - this is how the animal got its name. However, the older the shrew, the more its teeth wear down, and this color may gradually disappear. Dental formula of a shrew: incisors 3/2, canines 1/0, premolars 3/1, molars 3/3.

The ears are small, almost do not protrude above the surface of the coat. The eyes are black, but due to the predominantly underground lifestyle, vision is poor and poorly developed.

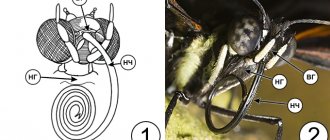

As a result, the animal searches for food using a powerful sense of smell or echolocation.

Shrews are one of the oldest branches of mammals, and their teeth have a clear division into canines, incisors, and molars.

REFERENCE! All animals of this species have a strong smell of musk, which is why many predators, having caught a shrew, refuse to eat it and throw it away.

The animal's prints are shallow, small, and usually arranged in pairs. When there is no hard crust on the snow, a clearly visible imprint of the tail remains.

Distribution[edit]

The Etruscan shrew inhabits a belt extending from 10° to 40° north latitude across Eurasia. [3] In Southern Europe, it has been found in Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, France, North Macedonia, Malta, Montenegro, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and Turkey, with unconfirmed reports in Andorra, Gibraltar and Monaco; it was introduced by humans to some European islands such as the Canary Islands. [2]

The shrew is also found in North Africa (Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia) and around the Arabian Peninsula (Bahrain, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Oman, Syria and Yemen, including Socotra). In Asia, it has been observed in Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Bhutan, China (Gengma County only), Burma, Georgia, India, Iran, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Laos, Malaysia (Malaysian part of Borneo island), Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Sri Lanka , Tajikistan, Thailand, Turkey, Turkmenistan and Vietnam. There are unconfirmed reports of the Etruscan shrew in West and East Africa (Guinea, Nigeria, Ethiopia) and in Armenia, Brunei, Indonesia, Kuwait, and Uzbekistan. [15]

Overall the species is widespread and not endangered, but its densities are generally lower than those of other shrews found in the area. [2] It is rare in some regions, especially in Azerbaijan, Georgia (listed in the Red Book), Jordan and Kazakhstan (Red Book). [5]

Links[edit]

- ^ ab Hutterer, R. (2005). Wilson, DE; Reader, D. M. (ed.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographical Guide (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. direct link

- ^ B s d e g Aulagnier, S., HUTTERER, R., Jenkins, P., Bukhnikashvili, A., Kryštufek, B. & Kock, D. (2017). Suncus etruscus

. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2022. doi: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T90389138A22288134.en - ^ B s d e e Jurgens, Klaus D. (2002). "Muscles of the Etruscan Shrew: Consequences of Small Size". Journal of Experimental Biology

.

205

(Pt 15): 2161–2166. PMID 12110649. - ^ abc Fons R.; Sender S.; Peters T.; Jurgens K.D. (1997). "Warming rates, heart and respiratory rates and their implications for oxygen transport during torpor arousal in the smallest mammal, the Etruscan shrew Suncus etruscus" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Biology

.

200

(Pt 10): 1451–1458. PMID 9192497. - ^ abcdefgh Suncus etruscus, Red Book of Kazakhstan

- ^ abcdef "Dwarf shrew (Suncus etruscus)". ours-nature.ru

(in Russian). - ^ abc "Vibrissal touch of an Etruscan shrew". Scholarpedia.org

. Retrieved March 21, 2013. - ^ ab Bloch, Jonathan I.; Rose, Kenneth D.; Gingerich, Philip D. (1998). "A new species of Batodonoides (Lipotyphla, Geolabididae) from the Early Eocene of Wyoming: the smallest known mammal". Journal of Mammology

.

79

(3):804–827. DOI: 10.2307/1383090. JSTOR 1383090. - ^ B s d e g h i JKL McDonald, DW; Barrett, P. (1993). Mammals of Europe. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09160-9.

- ^ abcdef Suncus etruscus. White-toothed Pygmy Shrew University of Michigan, Museum of Zoology

- Longevity records. Table 1. Record lifespan (years) for mammals, archived October 6, 2006, on the Wayback Machine. Demogr.mpg.de. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- Stone, R. David (1995) Eurasian insectivores and shrews: a status review and conservation action plan, IUCN, p. 30. ISBN 2-8317-0062-0

Interesting Facts

One interesting fact is known about the shrew. It is due to the fact that its smallest species live precisely where the harshest living conditions occur - the tundra, highlands, Siberia - and, logically, should strive for more favorable territories. Moreover, the size of the animal can be smaller the further north it lives - which contradicts Bergman’s rule, according to which the size of individuals should change upward due to cold. Many shrews in the northern regions are able to reduce the size of their internal organs during the winter in order to reduce heat loss.