Genus of crustaceans

| Daphnia | |

| Daphnia pulex | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Type: | Arthropods |

| Subtype: | Crustaceans |

| Class: | Branchiopods |

| Order: | Cladocera |

| Family: | Daphnia |

| Genus: | Daphnia Muller, 1785 |

| Subgenera | |

| |

| Diversity | |

| > 200 species | |

| Synonyms [1] | |

| |

Daphnia

, a genus of small planktonic crustaceans, are 0.2–5 mm (0.01–0.20 in) long.

Daphnia

are members of the order Cladocera, and are one of several small aquatic crustaceans commonly called water fleas because their loping (Wiktionary) swimming style resembles that of a flea.

Daphnia

live in a variety of aquatic environments from acidic swamps to fresh water lakes and ponds.

The two most accessible species of Daphnia

there are

D. pulex

(small and most common) and

D. magna

(large).

They are often associated with a related genus in the order Cladocera: Moina

, which is in the Moinidae family instead of Daphnia and is much smaller than

D. pulex

(about half its maximum length).

Daphnia

eggs for sale are usually enclosed in

an ephippium

(a thick shell consisting of two chitinous plates that contain and protect the winter eggs of the cladoceran).[2]

Appearance and characteristics

Play media

The beating heart

of Daphnia

under a microscope

Daphnia body

typically 1–5 millimeters (0.04–0.20 in) in length,[3] and is divided into segments, although this division is not visible.[4] The head is fused and usually slanted towards the body with a visible notch separating the two. In most species the rest of the body is covered by a shell, with an ventral cleft in which five or six pairs of legs lie.[4] The most notable features are the compound eyes, second antennae, and a pair of ventral setae.[4] Many species have translucent or nearly translucent carapace, making them excellent subjects for photography. microscope how you can observe the heartbeat.[4]

Even with relatively low power microscopy, it is possible to observe the feeding mechanism as immature young move in the brood pouch; In addition, the eye moves the ciliary muscles can be seen, and blood cells are pumped into the cardiovascular system by a simple heart.[4] The heart is located in the upper back, just behind the head, and the average heart rate is approximately 180 beats per minute under normal conditions. Daphnia

, like many animals, are prone to alcohol intoxication and can make excellent subjects for studying the effects of depressants on the nervous system due to their translucent exoskeleton and markedly altered heart rate.

They are tolerant of being seen alive under cover and appear to suffer no harm when returned to open water.[4] This experiment can also be done with caffeine, nicotine or adrenaline, each of which causes an increase in heart rate.[ citation needed

]

Due to its intermediate size, Daphnia uses both diffuse and circulatory methods to produce hemoglobin in low-oxygen environments.[5]

Daphnia as fish food

Due to its high nutrient content, daphnia is an excellent food for aquarium inhabitants. It is quite difficult to breed it under artificial conditions, so it is purchased in pet stores in live, frozen or dried form. In an aquarium, daphnia serves as excellent food for small or young fish. Dried crustaceans are completely ready for consumption; frozen daphnia are packaged in blisters and sold in pet stores. Eating crustaceans has a great effect on aquarium inhabitants. 50% of the weight of the crustacean consists of high levels of proteins. Its calorie content is similar to bloodworms, gammarus, caddisflies, amphipods, cyclops, and pond snails, but daphnia contains a high level of protein.

To breed daphnia in an aquarium you need the following:

- Select a special glass container that will hold from 1 to 3 liters, wash it thoroughly, and do not use abrasive substances.

- The water must be purified and free of chlorine and chemical impurities.

- The required water hardness should be from 5 to 17 degrees, pH from 7 to 8.

- An aquarium with daphnia must be kept away from direct light. The crustacean does not grow well in strong light. Using a 20-volt fluorescent lamp, you need to provide it with natural light throughout the day.

- The water temperature should be between 20 and 24 degrees. If the water is colder, it will not be able to reproduce.

Daphnia in the aquarium must be fully fed, dissolve the fertilizer in the water until it becomes cloudy, then add a new portion.

It is worth thoroughly cleaning the walls of the aquarium and changing the water if necessary. Oxygen must be supplied to the aquarium.

Daphnia is purchased in the form of eggs, then released into a container. When the eggs are ripe, they are caught using a net and used as feed, dried or frozen.

Systematics and evolution

Main article: List of Daphnia species

Daphnia

a large genus of over 200 species belonging to the cladoceran family Daphnia.[1]

Divided into several subgenera ( Daphnia

,

Australodaphnia

,

Ctenodaphnea

), but this division has been controversial and is still under development. Each subgenus was further divided into a number of species complexes. Understanding species boundaries is hampered by phenotypic plasticity, hybridization, intercontinental introductions, and poor taxonomic descriptions.[6][7][8]

External links [edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Daphnia . |

- Data related to Daphnia at Wikispecies

- Daphnia Genomics Consortium

- Daphnia: An Aquarist's Guide

- Waterflea.org: Community resource for cladoceran biology

- Daphnia species: taxonomy, facts, life cycle, links to GeoChemBio

| Taxon identifiers |

|

| Authoritative control |

|

Ecology and behavior

Anatomy of Daphnia pulex

Daphnia

The species is usually

p

-selected, meaning that they invest in early reproduction and therefore have a short lifespan.

Individual Daphnia

lifespan depends on factors such as temperature and abundance of predators, but can be 13–14 months in cold, oligotrophic fish-free lakes.[9] However, under typical conditions the life cycle is much shorter and usually does not exceed 5–6 months.[9]

Daphnia

typically filter feeders, ingesting mostly single-celled algae and various types of organic detritus, including protists and bacteria.[3][10] When kicked, a direct current is generated through the shell, which carries such material into the digestive tract.

Trapped food particles are converted into food. a bolus

which then moves down the digestive tract until it is expelled through the anus, located on the ventral surface of the terminal appendage.[10]

The second and third pair of legs are used in filter feeding of the organisms, ensuring that large, unabsorbable particles do not enter, while the other pairs of legs create a stream of water rushing into the organism.[10] Five trunk limbs used in filter feeding

Swimming is accomplished primarily by a second set of antennae, which are larger in size than the first set.[11] The action of this second set of antennae is responsible for the jumping movement.[11]

Daphnia

They are known to exhibit behavioral changes or modifications to their morphology in the presence of predator kairomones (chemical signals).

Some examples of morphological modifications include larger size at hatching, increased bulkiness, and development of "neck teeth". For example, juvenile D. pulex

will have a larger size after hatching, along with the development of cervical teeth on the back of the head, when in the presence of

Haoborus

kairomones.

These morphological defenses showed reduced mortality due to predation by Chaoborus, which is a limited-capacity predator. Chitin-related genes (deacetylases) are thought to play an important role in the expression/development of these morphological defenses in Daphnia

. Chitin-modifying enzymes (chitin deacetylases) have been shown to catalyze N-deacetylation of chitin, affecting the affinity of these chitin filaments for protein binding. [12]

Daphnia diet

Daphnia in water.

The main diet consists of yeast and blue-green bacteria. A large concentration of single-celled organisms can be found in a flowering pond where few fish live. They also feed on ciliates and detritus.

Water filtration occurs thanks to the thoracic legs. After this, food enters the abdominal cavity, and then into the esophagus. The salivary glands and secretions on the upper lips help glue food particles together into a lump.

The filtration rate of adults ranges from 1 to 10 ml per day. The amount of food is affected by body weight. An adult magna can eat 600% of its body weight.

Life cycle

Most Daphnia

species have a life cycle based on "cyclic parthenogenesis", alternating between parthenogenetic (asexual) reproduction and sexual reproduction.[3]

For most of the growing season, females reproduce asexually. They produce a brood of diploid eggs every time they moult; these broods may contain as few as 1-2 eggs in smaller species such as D. cucullata

, but may contain over 100 in larger species such as

D. magna

. Under typical conditions, these eggs hatch every other day and remain in the female's brood pouch for about three days (at 20 °C). They are then released into the water and undergo another 4–6 instars over 5–10 days (longer in poor conditions) until they reach the age at which they can reproduce.[3] Offspring produced asexually are usually female.

Cyclic parthenogenesis in cladocerans Daphnia greata

| female Daphnia with eggs Egg bag for rest ( ephippium ) and the newly hatched juvenile daphnid | Daphnia birth |

However, towards the end of the growing season, the mode of reproduction changes and females produce durable "resting eggs" or "winter eggs".[3] When environmental conditions deteriorate (such as overcrowding), some of the offspring produced asexually become males.[3] The females begin to produce haploid sex eggs, which the males fertilize. In maleless species, resting eggs are also produced asexually and are diploid. In either case, resting eggs are protected by a hardened shell called the ephippium

, and are thrown out during the next molting of the female. Ephippia can withstand periods of extreme cold, drought or lack of food, and when conditions improve, hatch as females (they can be classified as extremophiles).[3]

Breeding at home

Breeding crustaceans is not difficult. To do this, it is enough to create suitable conditions.

Containers for growing

To grow crustaceans at home, you can use containers with a volume of up to 20 liters, made of glass, propylene or stainless steel. If they are raised in a regular aquarium, the surface area must be large to allow for gas exchange.

Environment Settings

Daphnia can be grown in almost any conditions.

Crawfish feel most comfortable in water with the following parameters:

- Temperature. The water flea thrives in a body of water with a wide temperature range. The optimal water temperature is 18-24 degrees.

- Salinity. Daphnia is a freshwater crustacean, so the water in the container must be fresh.

- Oxygen. Under natural conditions, daphnia can live in ponds with dirty water, so oxygen levels can fluctuate from zero to very saturated. This endurance of organisms is associated with their ability to produce hemoglobin. Crayfish do not tolerate intense aeration with a large number of small bubbles. When the container is slowly saturated with oxygen, a layer of foam forms on the surface, which can be destructive.

- Ammonia. Even a small amount of ammonia has a negative effect on the body of daphnia and can affect the intensity of their reproduction.

- Minerals. Crawfish react sharply to changes in the chemical composition of water. A slight increase in the amount of zinc, magnesium or potassium in the aquatic environment can be detrimental to them. Thus, a slight increase in the amount of copper reduces the activity of daphnia, and phosphorus can cause the death of young individuals.

Aeration

Additional enrichment of water with oxygen is desirable when growing certain species. Aeration promotes the development of phytoplankton and prevents the formation of a film on the surface of the water. The air flow should be of medium intensity so as not to cause inconvenience.

What to feed

Under natural conditions, daphnia feeds on microplankton, bacteria and yeast.

To obtain bacteria, soak banana peels in warm water and leave for 6-7 days. When the water becomes cloudy, the nutrient medium can be added to the aquarium at the rate of 0.5 liters per 20 liters of water.

For feeding, you can use dry or wet baker's yeast, which is rich in nutrients. Feed is added at the rate of 28 grams per 20 liters of water daily.

Chlorella is used as microscopic algae, which inhabits almost all bodies of water. To breed such algae, it is enough to place a small amount of water from the aquarium in a warm, well-lit place. In such conditions, algae begin to actively reproduce.

To diversify the diet of crustaceans, it is recommended to add a small amount of beet, cabbage or carrot juice to the water, which will serve as an additional source of vitamins.

How to increase cultivation productivity

Growing daphnia at home is not difficult even for beginners.

To increase productivity, you should use the following recommendations:

- to aerate the container when breeding crustaceans, you should use an airlift filter used in cages with fry;

- water changes are carried out taking into account the feed used and the volume of the container; if the aquarium is large, then replace up to 30% of the water once every 7-10 days;

- regularly collect daphnia; this will help maintain constant reproduction and growth of crustaceans;

- the duration of daylight should be at least 18 hours; 24-hour lighting is ideal.

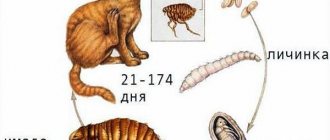

Parasites

Life cycle of Pasteuria ramosa

bacterial parasite of the cladoceran

Daphnia magnus

.

The diagram on the left shows the life cycle of Pasteuria ramos

bacterial parasite

Daphnia

.

Susceptible hosts become infected from spores in sediment or suspension. The parasite develops primarily in the body cavity and muscle tissue of the host, increasing in density and eventually expanding to occupy the entire host. Typical consequences for the owner are infertility and gigantism. The spores are released mainly after the host dies and sinks to the ground, and sometimes directly into the water by a lumbering predator. Daphnia magnus

infected with

Pasteuria ramosa

Reproduction of individuals

Daphnia are distinguished by the peculiarity of breeding offspring without fertilization. Females of this species have a brood chamber. It is protected by the edge of the shell and is located on the back. Under favorable conditions, an adult can lay 50 to 100 unfertilized eggs. They develop in the cavity, and only females, and leave it independently. In females, molting begins after this.

After a few days, the reproduction process begins to repeat. Adult individuals join this cycle, so everything happens very quickly. One female can give birth to offspring up to 25 times over the entire period of her life. Because of this, in the summer you can observe a reddish color of water in reservoirs where daphnia live. It is simply teeming with a huge amount of plankton.

With the onset of autumn, males join the breeding process. After fertilization, the shell on the eggs becomes denser. Future offspring are able to withstand frosts, as well as drying out water bodies, and spread with dust. When spring arrives, the breeding cycle begins to repeat again as females emerge. A new population of individuals may differ in body shape at different times of the year.

Uses

Daphnia

The species is a popular live food in tropical and marine fish farming.

They are often fed on tadpoles or small amphibian species such as the African dwarf frog ( Hymenochirus boettgeri

).

Daphnia

can be used in certain environments to test the effects of toxins on an ecosystem, making their indicator genus particularly useful due to its short lifespan and reproductive capabilities.

Because they are almost transparent, their internal organs are easy to study in living specimens (for example, studying the effect of temperature on heart rate). ectothermic organisms). Daphnia

is also commonly used for experiments testing climate change aspects such as ultraviolet radiation (UVR), which seriously damage zooplankton species (eg, reduced feeding activity[14]).

Because of their thin membrane, which allows drugs to be absorbed, they are used to monitor the effects on the heart of certain drugs, such as epinephrine or capsaicin.

Invasive species

Fishhook waterflea (above) and Bythotrephes longimanus (spiny water flea) (below)

Some species of Daphnia have evolved permanent, temporary defenses against being eaten by fish, such as spines and long hooks on the body, which also cause them to become entangled in fishing line and cloud water from - because of their large number. Species such as Daphnia lumholtz

[15][16][17][18] (native to East Africa, the Asian subcontinent of India and eastern Australia) have these characteristics and great care should be taken to prevent their further spread into North American waters.

Some Daphnia species native to North America may develop sharp spines on the end of their bodies and helmet-like structures on their heads when exposed to predators.[19][20] but in general this is temporary for these Daphnia species and they do not completely suppress or prevent native predators from eating them. Although daphnia are an important base of the food chain in freshwater lakes (and vernal pools), they become a nuisance when they cannot be eaten by native macroscopic predators, and there is some concern that the original spineless and hookless water fleas and daphnia are running out. surpassed the aggressive ones. (This may not be the case, however, and the new invaders may mostly be a nuisance for tangling and clogging.)

Places and living conditions

These cladocerans can be found in all ponds and lakes in different parts of the world.

Character and lifestyle

Large accumulations of crustaceans are observed in temporary reservoirs - ditches, puddles, small lakes with stagnant water. Getting into water even with a weak current, daphnia filter suspended particles of soil and clog the intestines. This makes it difficult for them to move and causes their death.

Crayfish spend most of their lives in the water column. Some species, filtering water, feed on microscopic algae, while others live near the bottom and eat dead particles of plants and invertebrates. Some varieties, halophiles, easily tolerate drought by hibernating.

These creatures are very voracious. The daily volume of food consumed can reach 600% of their own weight. Daphnia's main diet consists of bacteria, yeast and blue-green algae. The largest concentrations of crustaceans are observed in reservoirs with “blooming” water, where they reproduce especially intensively.

Daphnia reacts sharply to lighting. In bright light, it tries to stay closer to the bottom of the reservoir.

References

- ^ a b

A. Kotov;

L. Forro; Korovchinsky N. M.; A. Petrusek (March 2, 2012). "Checklist of Crustaceans-Cladocera" (PDF). World List of Freshwater Species of Cladocera

. Belgian Biodiversity Platform. Retrieved October 29, 2012. - N. N. Smirnov (2014). Physiology of Cladocera

. Amsterdam: Academic Press. - ^ a b c d f f d

Dieter Ebert (2005).

"Introduction to Daphnia

biology".

Ecology, epidemiology and evolution of parasitism in

Daphnia. Bethesda, MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information. ISBN 978-1-932811-06-3. - ^ a b c d f f

"

Daphnia

".

Oneida Lake Education Initiative

. Stony Brook University. Retrieved October 9, 2013. - van Bergen, Ifke (2004). “DAPHNIA BREATHES EASILY.” biology.org

. Retrieved 2018-04-11. - Niles Lehman; Michael E. Pfrender; Philip A. Morin; Teresa J. Crisis; Michael Lynch (1995). "Hierarchical molecular phylogeny within the genus Daphnia

."

Molecular phylogenetics and evolution

.

4

(4): 395–407. Doi:10.1006/mpev.1995.1037. PMID 8747296. - Derek J. Taylor; Paul D. N. Hebert; John C. Colborne (1996). "Phylogenetics and evolution of Daphnia long

group (crustaceans) based on 12S rDNA sequence and allozyme variation" (PDF).

Molecular phylogenetics and evolution

.

5

(3): 495–510. Doi:10.1006/mpev.1996.0045. PMID 8744763. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-04-18. - Sarah J. Adamowicz; Paul D. N. Hebert; Maria Cristina Marinone (2004). "Species diversity and endemism in Daphnia

of Argentina: a genetic study."

Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society

.

140

(2):171–205. Doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2003.00089.x. - ^ a b

Barbara Pietrzak;

Anna Bednarskaya; Magdalena Markovska; Maciej Rojek; Ewa Szymanska; Miroslav Slusarchik (2013). "Behavioral and physiological mechanisms of extremely long life in Daphnia

."

Hydrobiology

.

715

(1):125–134. Doi:10.1007/s10750-012-1420-6. - ^ a b c

Z. Maciej Gliwicz (2008).

"Zooplankton". In Patrick O'Sullivan; C. S. Reynolds (ed.). Handbook of Lakes: Limnology and Limnetic Ecology

. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 461–516. ISBN 978-0-470-99926-4. - ^ a b

Stanley L. Dodson;

Carla E. Caceres; D. Christopher Rogers (2009). "Cladocera and other Branchiopoda". In James H. Thorpe; Alan P. Kovic (ed.). Ecology and classification of freshwater invertebrates of North America

(3rd ed.). Academic press. pp. 773–828. ISBN 978-0-08-088981-8. - Kristiani, Mark (2016). "Phenotypic plasticity of three Daphnia genotypes in response to predator kairomone: evidence for the involvement of chitin deacetylases." Journal of Experimental Biology

.

219

(Pt 11): 1697–704. Doi:10.1242/jeb.133504. PMID 26994174. S2CID 36557263. - C. Michael Hogan (2008). " Makgadikgadi

".

Megalithic portal

. - Fernandez, Carla Heloise; Reyas, Danny (2017-04-05). "Effects of UV-B radiation on grazing by two cladocerans from high Andean lakes." PLOS ONE

.

12

(4):e0174334. Doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0174334. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5381789. PMID 28379975. - USGS: Non-native aquatic species: Daphnia lumholtzi

- Center for Freshwater Biology - University of New Hampshire: Daphnia lumholtz

- ISSG: Global Invasive Species Database: Daphnia lumholtzi (crustacean)

- James A. Stockel, Illinois Natural History Survey: Daphnia lumholtzi: the next Great Lakes exotic? Archived 2016-12-20 in the Wayback Machine

- Elizabeth A. Colburn (2004), Vernal Pools: Natural History and Conservation

, page 118 of the 2008 2nd paperback edition. - Patrick Lavens and Patrick Sorgeloos, Guide to the Production and Use of Live Food for Aquaculture: Daphnia and Moina