- Wild animals

- >>

- Insects

A louse is a group of small, wingless insects. Parasites are divided into two main groups: chewing or biting lice, which are parasites of birds and mammals, and sucking lice, which are parasites of mammals only. One of the sucking lice, the human louse, lives in filthy and overcrowded conditions and is a carrier of typhoid and relapsing fever.

Origin of the species and description

Photo: Louse

It is generally accepted that lice are descended from book lice (order Psocoptera). It is also recognized that chewing lice are related to sucking lice; some researchers believe that they evolved from offspring before division into species, others that they differed from species already parasitizing mammals. The origin of elephant lice is unclear.

Apart from lice eggs found in Baltic amber, there are no fossils that can provide information about the evolution of lice. However, their distribution is somewhat similar to the history of fossils.

The genus of chewing louse often has a number of species that are limited to a single bird species or a group of closely related birds, suggesting that the genus assigned to the order of birds was parasitized by an ancestral stock of chewing louse that diverged and evolved along with the divergence and evolution of its avian hosts .

Video: Louse

This relationship between host and parasite may shed some light on the relationship between the hosts themselves. Flamingos, which are usually housed with storks, are parasitized by three genera of sucking lice, found elsewhere only in ducks, geese and swans, and may therefore be more closely related to these birds than to storks. The louse closest to the human body louse is the chimpanzee louse, while in humans it is the gorilla pubic louse.

However, a number of factors have obscured the direct relationship between lice species and host species. The most important of these is secondary infestation, which is the emergence of lice species on a new and unrelated host. This could have occurred at any stage of host or parasite evolution, so that the subsequent divergence obscured all traces of the original host change.

The length of the flattened bodies of lice ranges from 0.33 to 11 mm, and they are whitish, yellow, brown or black. All bird species probably have chewing lice, and most mammals have chewing or sucking lice, or both.

How do linen lice differ from other parasitic insects that plague humans?

Distinctive signs of lice from fleas: light coloring, inability to jump.

Unlike bedbugs, lice are smaller and lighter in color. Bedbugs bite only at night, lice bite whenever they want, the main thing is that the person is dressed. Lice differ from ticks by being lighter in color and living in groups. A tick has 8 legs, a louse has 6.

You can hardly tell a body louse from a head louse, they are very similar. The pubic louse looks like a small crab. Diseases carried by linen lice

Linen lice are the most insidious and dangerous in terms of infecting humans with various diseases. The reason is very obvious - linen lice are very common in people who lead an unsanitary lifestyle. In addition to body lice, such people often have other diseases. Linen lice bites are dangerous:

- The appearance of unpleasant itching;

- Allergic rashes all over the body;

- Irritability in children;

- Ulcers;

- Pyoderma;

- Scratching leads to the development of infections.

It is not uncommon for body lice to carry the pathogens of typhus, relapsing fever, and Volyn fever.

Appearance and features

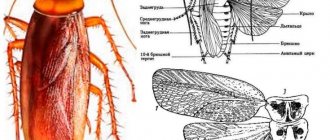

Photo: What a louse looks like

The body of the louse is dorsoventrally flattened with the long horizontal axis of the head, allowing it to lie close along the feathers or hairs for attachment or feeding. The shape of the head and body varies considerably, especially in the chewing louse of birds, in adaptation to different ecological niches on the host's body. Birds with white plumage, such as swans, have a white louse, while a cat with dark plumage has a louse that is almost entirely black.

The antennae of the louse are short, three to five segments, sometimes in the male they are modified as compressive organs to hold the female during mating. The mouths are adapted for biting in biting lice and highly modified for sucking in sucking lice. Sucking lice have three spines, which are located in a sheath inside the head, and a small trunk armed with recursive tooth-like processes, probably for holding the skin while feeding.

Elephant lice have chewing mouth parts, with modified mouths that have a long proboscis at the end. The thorax may have three visible segments, may have a fusion of the mesothorax and methorax, or all three may be fused into one segment, as in sucking lice. The paws are well developed and consist of one or two segments. The birds inhabited by the chewing louse have two claws, and some of the colonies infested by mammals have a single claw. Sucking lice have one claw opposite the tibial process, which forms an organ that compresses the hair.

The louse's abdomen has eight to 10 visible segments. There is one pair of thoracic respiratory pores (spiracles) and a maximum of six abdominal pairs. Estable male genitalia provide important characters for species classification. The female does not have a distinct ovipositor, but various lobes present on the last two segments of some species may serve as guides for the eggs during laying.

The alimentary canal consists of the esophagus, a well-developed midgut, a smaller hindgut, four Malpighian tubules and a rectum with six papillae. In sucking lice, the esophagus passes directly into the large midgut with or without swelling. There is also a strong pump connected to the esophagus to suck in blood.

Recommendations

- ^ a b c

Hoell, H.V.;

Doyen, J.T.; Purcell, A. H. (1998). Introduction to Insect Biology and Diversity

(2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 407–409. ISBN 978-0-19-510033-4. - University of Utah (2008). Ecology and evolution of transmission in feathered lice (Phthiraptera: Ischnocera)

. pp. 83–87. ISBN 978-0-549-46429-7. - ^ a b c d e

Capinera, John L. (2008).

Encyclopedia of Entomology

. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 838–844. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1. - Gullan, P.J.; Cranston, P. S. (2014). Insects: An Essay on Entomology

. Wiley. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-1-118-84615-5. - Smith, Vince. "Phthiraptera: Summary". Phthiraptera.info. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- Mumcuoglu, Costa Y. (1999). "Prevention and treatment of pediculosis in children." Pediatric drugs

.

1

(3): 211–218. Doi:10.2165/00128072-199901030-00005. PMID 10937452. S2CID 13547569. - Rozha (1997). "Patterns of abundance of bird lice (Phthiraptera: Amblycera, Ischnocera)" (PDF). Journal of Avian Biology

.

28

(3):249–254. Doi:10.2307/3676976. JSTOR 3676976. - Rekasi J; and others. (1997). "Distribution patterns of bird lice (Phthiraptera: Amblycera, Ischnocera)" (PDF). Journal of Avian Biology

.

28

(2): 150–156. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.506.730. Doi:10.2307/3677308. JSTOR 3677308. - Felso B; and others. (2006). "Decreases in taxonomic diversity of lice (Insecta: Phthiraptera) in diving birds" (PDF). Journal of Parasitology

.

92

(4):867–869. Doi:10.1645/ge-849.1. PMID 16995408. S2CID 31000581. - Felso B; and others. (2007). "Diving behavior reduces the abundance of mammalian louse species (Insecta: Phthiraptera)" (PDF). Acta Parasitologica

.

52

: 82–85. doi:10.2478/s11686-007-0006-3. S2CID 38683871. - Møller AP; and others. (2005). "Parasite Biodiversity and Host Defense: Chewing Lice and the Immune Response of Their Avian Hosts" (PDF). Oecologia

.

142

(2):169–176. Doi:10.1007/s00442-004-1735-8. PMID 15503162. S2CID 12992951. - Møller AP; and others. (2010). "Ectoparasites, genitourinary glands and hatching success in birds" (PDF). Oecologia

.

163

(2):303–311. Doi:10.1007/s00442-009-1548-x. PMID 20043177. S2CID 11433594. - ^ a b

Roja (1993).

"Modes of speciation of ectoparasites and" random "lice" (PDF). International Journal of Parasitology

.

23

(7):859–864. Doi:10.1016/0020-7519(93)90050-9. PMID 8314369. - Paterson A.M.; and others. (1999). “How often do bird lice miss a boat? Implications for coevolutionary research" (PDF). Systematic biology

.

48

: 214–223. Doi:10.1080/106351599260544. - MacLeod C; and others. (2010). “The parasites got lost—did the invaders miss the boat or drown on arrival?” Letters on Ecology

.

13

(4):516–527. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01446.x. PMID 20455925. - Rozsa L; and others. (1996). "Relationship of Host Coloniality to Population Ecology of Bird Lice (Insecta: Phthiraptera)" (PDF). Journal of Animal Ecology

.

65

(2):242–248. Doi:10.2307/5727. JSTOR 5727. - Brown CR; and others. (1995). "Ectoparasites reduce long-term survival of their avian host" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London

B.

262

(1365):313–319. doi:10.1098/rspb.1995.0211. S2CID 13869042. - Bartlett, C. (1993). "Lice ( Amblycera

and

Ischnocera

) as vectors of

Eulimdan

species (Nematoda: Filarioidea) in Charadriiform birds and the requirement for short reproductive periods in adult worms."

Journal of Parasitology

.

75

(1):85–91. Doi:10.2307/3283282. JSTOR 3283282. - DT booth; and others. (1993). "Experimental demonstration of the energetic cost of parasitism in free-living hosts" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London

B.

253

(1337): 125–129. doi:10.1098/rspb.1993.0091. S2CID 85731062. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-10. Retrieved 2010-08-14. - Clayton (1990). "Mate selection in experimentally parasitized rock pigeons: the lousy males lose" (PDF). American zoologist

.

30

(2): 251–262. Doi:10.1093/icb/30.2.251. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-10. Retrieved 2010-08-14. - Garamszegi LZ; and others. (2005). "Age-related health status and song characteristics." Behavioral Ecology

.

16

(3):580–591. Doi:10.1093/beheco/ari029. - Topor, Peter (2013). Multicellular Animals: Volume II: Phylogenetic System of Metazoa

. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 303–307. ISBN 978-3-662-10396-8. - ^ a b

Smith, Vince. Phthiraptera.info. International Society of Phthirapterists. Retrieved October 25, 2015. - Banks, Jonathan K.; Paterson, Adrian M. (2004). "Phylogeney of the penguin chewing louse (Insecta: Phthiraptera) based on morphology". Taxonomy of invertebrates

.

18

(1):89–100. Doi:10.1071/IS03022. S2CID 53516244. - Wappler, T.; Smith, W. S.; Dalglish, R. C. (2004-08-07). "Scratching an Ancient Itch: A Fossil of an Eocene Bird Louse." Proceedings of the Royal Society of London.

Series B: Biological Sciences .

271

(suppl_5): S255 – S258. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2003.0158. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1810061. PMID 15503987. - ^ a b c d

Reed D.L.;

Light, J.E.; Allen, J.M.; Kirchman, J. J. (2007). "A Pair of Lice Lost or Parasites Regained: The Evolutionary History of Anthropoid Primate Lice." BMC Biology

.

5

(7): 7. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-5-7. PMC 1828715. PMID 17343749. - ^ a b

Parry, Wynne (7 November 2013). "Lice hold keys to human evolution." LiveScience. Retrieved October 25, 2015. - ^ a b

Kittler, R.;

Kayser, M.; Stoneking, M. (2003). "Molecular evolution of Pediculus humanus

and the origin of clothing".

Current Biology

.

13

(16): 1414–1417. Doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00507-4. PMID 12932325. S2CID 15277254. - Shao, R.; Zhu, X.Q.; Barker, S.C.; Hurd, K. (2012). "Evolution of highly fragmented mitochondrial genomes in human lice". Genomic biology and evolution

.

4

(11): 1088–1101. Doi:10.1093/gbe/evs088. PMC 3514963. PMID 23042553. - ^ a b

Light, J. E.;

Allen, J.M.; Long, L.M.; Carter, T.E.; Barrow, L.; Suren, G.; Raoult, D.; Reed, D.L. (2008). "Geographic distribution and origin of human lice ( Pediculus humanus capitis

) based on mitochondrial evidence."

Journal of Parasitology

.

94

(6):1275–1281. Doi:10.1645/GE-1618.1. PMID 18576877. S2CID 9456340. - (Kluge 2005, Kluge 2010, Kluge 2012):

- Kowalski, Todd J.; Agger, William A. (2009). "Art Supports New Plague Science." Clin.

Infect. Dis .

48

(1): 137–138. Doi:10.1086/595557. PMID 19067623. - Elliott, Lynn (2004). Clothing in the Middle Ages

. Crabtree. paragraph 29. ISBN 978-0-7787-1351-7. - Hooke, Robert. "Microscopic view of a louse." Royal Society. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- Sarason, Lisa T. (2010). The Natural Philosophy of Margaret Cavendish: Reason and Fantasy during the Scientific Revolution

. JHU Press. pp. 165–167. ISBN 978-0-8018-9443-5. Bear-men were to be her experimental philosophers, bird-men her astronomers, fly-men her naturalists, ape-men her chemists, satyrs her galenical doctors, fox-men her politicians. , Spider-Man and Lice are her mathematicians, Jackdaws - Magpie - and parrot people are her speakers and logicians, Gyants are her architects, etc. - Cavendish, Margaret (1668). Description of a new world called the Burning World

. A. Maxwell. - Zinsser, Hans (2007) [1935]. Rats, lice and history

. Transaction publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-0672-5. - Altshuler, Deborah Z. (1990). "Zinsser, lice and history." HeadLice.org. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- Evans, Richard J. "The Great Unwashed." Gresham College. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- Weinstein, Philip. “Entomophobia / illusory parasitosis; illusory parasitosis." Department of Medical Entomology, University of Sydney. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- Kirkness, Ewen F.; and others. (2010). “The genome sequences of the human body and its primary endosymbiont provide insight into a persistent parasitic lifestyle.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America

.

107

(27):12168–12173. doi:10.1073/pnas.1003379107. PMC 2901460. PMID 20566863. - Pittendry, Barry R.; Berenbaum, May R.; Seufferheld, Manfredo J.; Margam, Venu M.; Strycharz, Joseph P.; Yoon, Kyung S.; Sun, Vaylin; Renan, Robert; Lee, Si Hyuk; Clark, John M. (2011). “Simplify, simplify: lifestyle and the compact body genome provide unique opportunities for functional genomics.” Communication and Integrative Biology

.

4

(2): 188–191. doi:10.4161/cib.4.2.14279. PMC 3104575. PMID 21655436. - William White (1859). Notes and requests

. Oxford University Press. pp. 275–276. - Pearce, Helen (2004). "Indecent Pictures: Political Graphic Satire in England, c. 1600 - approx. 1650" (PDF). York University. Magazine citation required | log = (help)

- Joyce, James (1939). Finnegans Wake

. Faber. paragraph 180. - Trafzer, Clifford E. (2015). Song of the Chemehuevi: The Resilience of the Southern Paiute Tribe

. University of Washington Press. pp. 22–25. ISBN 978-0-295-80582-5. - ^ a b

Carroll, Jim. "Claire's Songs: Kilkenny's House of Lice." Claire's library. Retrieved October 19, 2015. - Scott, Bruce (2013). "My Colleen on the Shore" (PDF). Veteran. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- Twinn, Cecil Raymond (1942). The Life of Insects in the Poetry and Drama of England: With Special Reference to Poetry

. University of Ottawa (Doctoral dissertation). HDL:10393/21088.

Where does the louse live?

Photo: Insect louse

Many birds and mammals are infested with more than one type of lice. They often have at least four or five types of lice. Each species has certain adaptations that allow it to live in certain areas of the host's body. Among avian chewing lice, some species occupy different areas of the body for resting, feeding, and laying eggs.

Interesting Fact: The louse cannot live for shorter periods of time away from its host, and adaptations serve to keep it in close contact. The louse is attracted by body heat and repelled by light, which causes it to remain in the warmth and darkness of the host's plumage or husk. She is also likely sensitive to her host's scent and the characteristics of the feathers and hairs that help lice navigate.

A louse may temporarily leave its host to move to another host of the same species or to a host of a different species, such as from prey to predator. Chewing lice are often attached to flying lice (Hippoboscidae), which also parasitize birds and mammals, as well as other insects, with the help of which they can be transferred to a new host.

However, they may not be able to establish themselves on a new host due to chemical or physical incompatibility with the host in terms of food or habitat. For example, some mammalian lice can only lay eggs on hairs of the appropriate diameter.

The infrequency of transmission from one host species to another results in host specificity or host limitation, in which a particular louse species is found in only one host species or a group of closely related host species. It is likely that some host-specific species evolved as a result of isolation because there was simply no opportunity for lice to be transmitted.

Pets and zoo animals sometimes have populations of lice from different hosts, and pheasants and partridges often have thriving populations of chicken lice. Heterodoxus spiniger, which parasitizes domestic dogs in tropical regions, was most likely acquired relatively recently from an Australian marsupial.

Now you know where the louse lives. Let's see what this insect eats.

Prevention of lice infestation

It is much easier and safer to prevent an infestation of linen lice than to deal with them later. To avoid or minimize infestation with linen lice, you must:

- Avoid declassed individuals;

- Store clothes carefully;

- Avoid being in rooms where unsanitary conditions reign;

- Clothes purchased second-hand must be washed at the highest possible temperature;

- Exercise maximum caution on public transport;

- Keep your distance from people who are clearly not practicing good hygiene.

What does a louse eat?

Photo: Lice

Sucking lice feed exclusively on blood and have mouthparts well adapted for this purpose. Fine needles are used to pierce the skin, where salivary secretions are injected to prevent coagulation as blood is sucked into the mouth. The needles are retracted into the head when the louse is not eating.

Chewing bird lice feed on:

- feathers;

- blood;

- tissue fluids.

They obtain fluids by gnawing on the skin, or, like bird lice, from the central pulp of a developing feather. Feather-eating chewing lice are able to digest keratin from feathers. It is likely that mammalian chewing lice feed not on fur or hair, but on skin debris, secretions, and perhaps occasionally blood and tissue fluids.

Lice infestations develop mainly during the cold season and reach a peak in late winter and early spring. Skin temperature is also related to the severity of a louse infestation. The number of lice decreases in the hot season. Poor diet in winter weakens cattle's natural defenses against lice infestation. Denser and wetter fur in winter creates excellent conditions for the development of lice.

In the spring, food is found quickly when the herds begin to graze on new pastures. Shorter coats and sun exposure reduce skin moisture, and free grazing results in overcrowding in winter quarters, which also reduces transmission. As a consequence, lice infestations usually decrease spontaneously during the summer season. However, a few lice usually survive on some animals, which re-infect the entire herd when they return to hibernate the following winter.

Preventive measures

Pediculosis must be avoided by preventive measures, and not hope that “maybe it will go away.”

The following measures significantly reduce the risk of infection and development of the disease;

Maintaining personal hygiene:

- Mandatory washing of the entire body at least once a week.

- Do not keep wearing the same clothes and wash them often. For greater effect, it is advisable to iron it with an iron.

- Don't neglect cutting and combing your hair.

- Use only personal hygiene items.

- Avoid head-to-head contact with strangers or unfamiliar people, as well as promiscuous casual sexual contact.

- Constant change and washing of bed linen: Change linen at least once every 2-4 weeks. Wash it every time you change clothes.

Let's celebrate! Pediculosis is an insidious disease that may not show itself for a long time. At the first signs, you should immediately contact a specialist.

Features of character and lifestyle

Photo: White louse

Lice spend their entire lives on the same hosts: transmission from one host to another occurs through contact. Transmission from herd to herd usually occurs by introducing an infested animal, but flies can also sometimes transport lice.

Up to 1-2% of cattle in a herd may carry large numbers of lice even in the summer when high temperatures reduce lice numbers. These animal carriers are a source of reinfection during cold spells. This is usually a bull or cow in poor condition. Winter housing provides ideal conditions for the transfer of lice between livestock.

Fun Fact: Disease outbreaks caused by lice were common byproducts of famine, war, and other disasters before the advent of insecticides. Due in part to the widespread use of insecticidal shampoos for control, the head louse is resistant to many insecticides and is making a resurgence in many regions of the world.

A severe lice infestation can cause severe skin irritation, and damage to the outer ball of skin can lead to secondary infections. Chafing and damage to hides and fur may also occur in pets, and meat and egg production may be reduced. Heavily infected birds may have very damaged feathers. One of the dog's lice is an intermediate host of the tapeworm, and the rat louse is a transmitter of murine typhus in rats.

Social structure and reproduction

Photo: Black louse

With the exception of human body lice, lice spend their entire life cycle, from egg to adult, on a host. Females are usually larger than males and often outnumber them on a single host. In some species, males are rare and reproduction occurs with unfertilized eggs (parthenogenesis).

Eggs are laid singly or in clumps, usually attached to a feather or hair. The human louse lays eggs on clothing near the skin. Eggs may be simple ovoid structures, glistening white among feathers or hairs, or may be heavily sculptured or decorated with projections that help anchor the egg or serve for gas exchange.

When the larva inside the egg is ready to hatch, it sucks in air through its mouth. Air passes through the alimentary canal and accumulates behind the larva until sufficient pressure is created to press down the lid of the egg (the gill callus).

In many species, the larvae also have a sharp lamellar structure, an incubation organ in the head region, which is used to open the gill bone. The emerging larva is similar to the adult, but is smaller and uncolored, has fewer hairs, and differs in some other morphological details.

Metamorphosis in lice is simple, the larvae molt three times, each of the three stages between moults (instars) becoming larger and more similar to the adult. The duration of the various developmental stages varies from species to species and within each species depending on temperature. In human louse, the egg stage can last from 6 to 14 days, and the hatching to adult stages can last from 8 to 16 days.

Interesting fact: The life cycle of a louse can be closely related to the specific habits of the host. For example, the elephant seal louse must complete its life cycle within three to five weeks, twice a year, which the elephant seal spends on the shore.

How to recognize lice

In the first days and even weeks after infection, it is quite difficult to notice anything. But after the adults give birth, and sexually mature lice emerge from the nits and the population rapidly increases, the number of bites also increases, and with it the inconvenience. Pediculosis is indicated by:

- • active itching mainly on the hairy parts of the body (there are head, body and pubic lice, which can spread throughout the body);

- • grayish-blue spots on the skin;

- • non-healing scratches;

- • restlessness and irritability;

- • small pustules in places of scratching.

Scratching is dangerous, as it can be accompanied by an infection - as a result, whole areas of inflammation can appear on the skin. In addition, head and body louse are carriers of relapsing and typhus, as well as several other dangerous diseases. Nowadays, this is rather a rarity, but the risk of encountering a parasite that carries the disease still exists, so we need to seriously combat pediculosis.

Natural enemies of lice

Photo: What a louse looks like

The enemies of lice are the people who fight them. Classic dip and spray concentrates of traditional contact insecticides (mainly organophosphates, synthetic pyrethroids and amidines) are quite effective lacicides for cattle. However, such insecticides do not kill lice eggs (nits), and their residual effect is usually not sufficient to ensure that immature lice are killed when the eggs hatch.

A variety of compounds are effective in controlling lice in cattle, including the following:

- synergized pyrethrins;

- synthetic pyrethroids;

- cyfluthrin;

- permethrin;

- zeta-cypermethrin;

- cyhalothrin (including gamma and lambda cyhalothrin, but only for cattle).

Many pyrethroids are lyophilic, facilitating the development of pour-on formulations with good distribution. Natural pyrethrins degrade quickly, while synthetic pyrethroids such as flumethrin and deltamethrin are more stable and have a relatively long duration of action, but they do not affect all stages of the lice life cycle.

Organophosphates such as phosmet, chlorpyrifos (for beef and non-lactating dairy cattle only), tetrachlorvinphos, coumaphos, and diazinon (for beef and non-lactating dairy cattle only) are also used against lice.

Compounds such as macrocyclic lactones, ivermectin, eprinomectin and doramectin are used to control lice in cattle. Injectable macrocyclic lactones also control lice bites as they reach the parasites through the host's bloodstream. But control of chewing lice is usually incomplete. Medicinal formulations are effective against lice bites, while injectable formulations are primarily effective against blood-sucking lice.

Addition about nits

Each type of lice nits has its own characteristics:

- Head louse nits are up to 0.8 mm in size, elongated in shape and light in color, due to which in the early stages they can be confused with dandruff. As the eggs mature, they darken and enlarge;

- Body lice eggs have an oblong shape, up to 0.5 mm long. Females lay them in the most inaccessible places of clothing, and therefore it is very difficult to detect oviposition;

- Pubic lice nits are dark in color and have a pointed shape, resembling a tiny droplet.

Very often it is difficult for people to understand what they have found on their hair: nits or dandruff. There are several differences between nits and dandruff:

- Dandruff is very easy to remove from hair: just shake the curl or comb it. When manipulating the hair, the nits do not move from their place because they are well glued.

- The nits are oval in shape, their color varies from whitish to brown, and the sizes are the same. Dandruff is always white in color and its size can vary.

- The eggs are located closer to the skin, where there is more warmth; the places where oviposition is most concentrated are the back of the head and the area behind the ears. Dandruff is located in any part of the head.

- Pediculosis causes unbearable itching, which causes skin damage. There is also itching from dandruff, but it is less noticeable and therefore does not leave visible damage.

Nits resemble dandruff